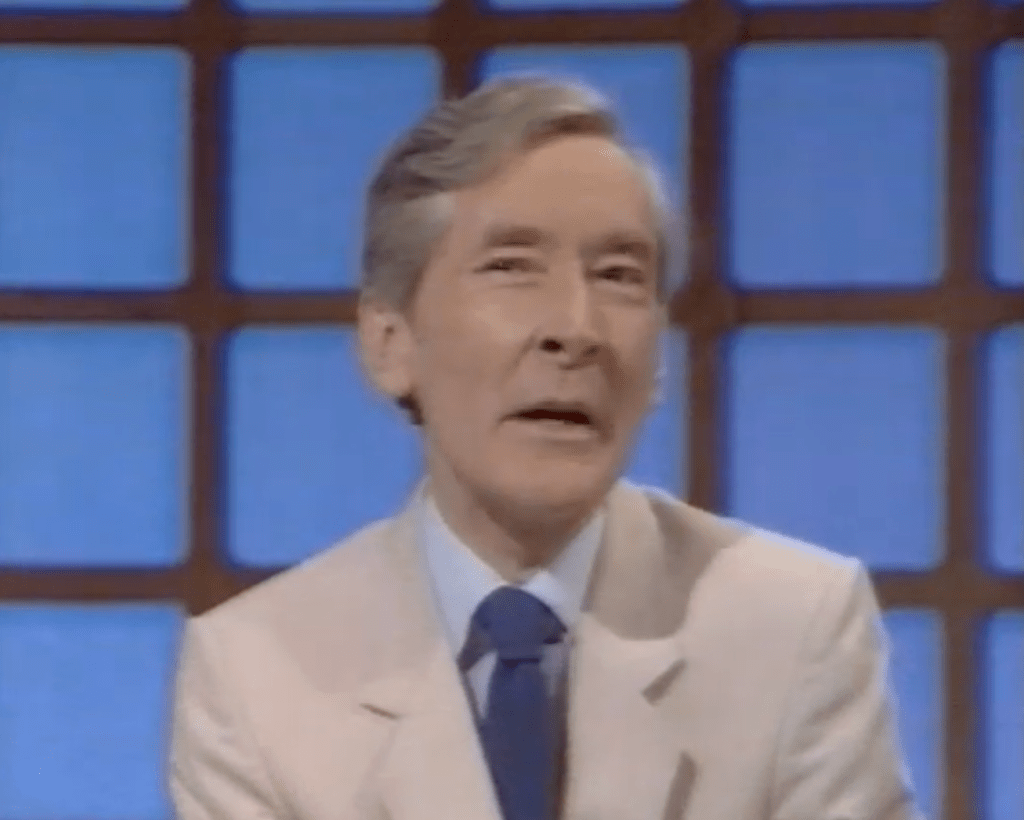

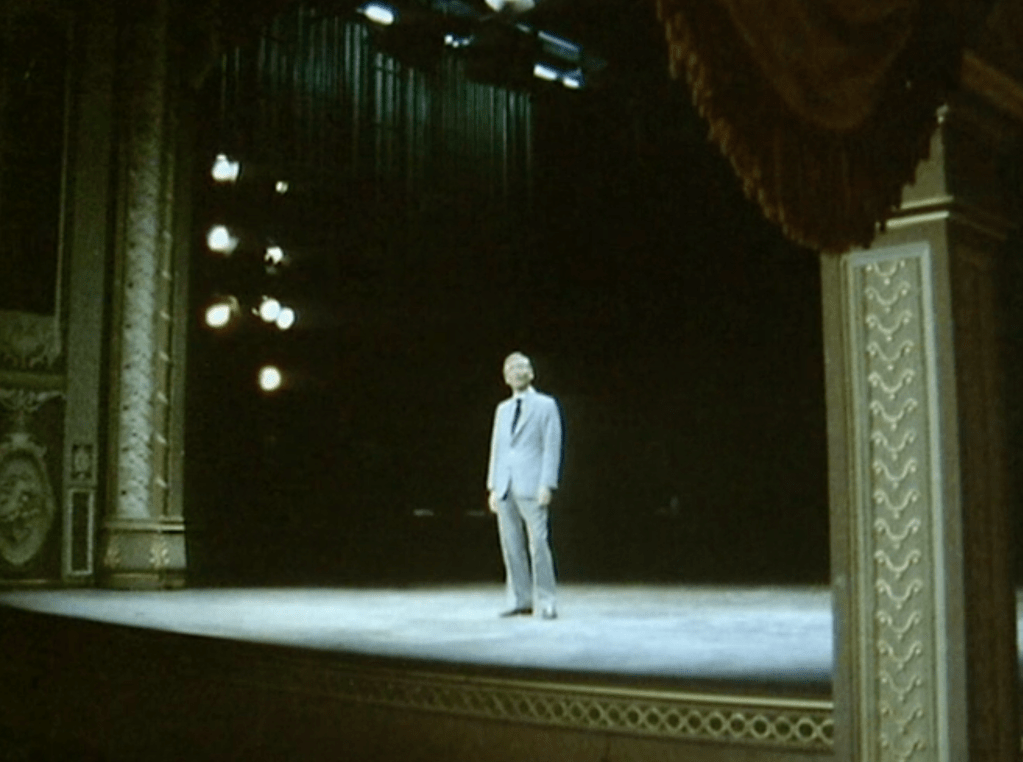

Kenneth Williams hosting Wogan, BBC1, 23 April 1986

Between January 1980 and his death in April 1988, Kenneth Williams appeared as a guest on 56 different television programmes.

If you include other TV work, such as narrations, dramatic roles and contributions to news reports and documentaries, the total climbs to 78. Add in return visits to the same show, then you’re looking at a figure of least 220 separate appearances.

Has any other person in the history of broadcasting graced so many programmes within such a short period of time and across such contrasting formats? No one springs to mind. And even if somebody has notched up a similar tally, could they match the range? From bawdy children’s series to fusty book reviews; from glitzy light entertainment to sombre religious reflection; and from chat shows of all size and distinction to dozens upon dozens of panel games – all in the space of eight years and three months.

For Williams, someone who by the 1980s had already seen success come and go in film, theatre and radio, such accomplishment probably meant little statistically. His posthumously-published diaries reveal inconsistent attitudes towards family, friends, colleagues and showbusiness itself – but rarely towards money. Television provided first and foremost a means of financial support. If another stint on Whose Baby? kept the pennies coming in, so be it.

But thank goodness he wasn’t choosy. Those 220-plus appearances may not all have been an unqualified success, but they all had something to offer – even if it was the sight of a man preparing aubergines with Nanette Newman, or climbing inside a giant polystyrene replica of his own nose.

Capable of broad humour and deep insight within a single anecdote, Williams had a way of ensnaring your senses the moment his voice drifted into earshot. What he said on television could often be upstaged by how he said it, but that didn’t matter: it was as much of a treat – a privilege, surely – to watch him as to hear what he had to say.

We can also be thankful he embraced television when he did and no later. Williams shunned TV almost entirely during his early career, preferring instead to try and be a bright young thing, trolling round repertory theatres, accepting bit parts in films and fighting his way through song-and-dance routines in stage revues.

What a waste – a crime! – had he settled into panto and summer season for the rest of his days. Instead he turned to television in the 1960s, grudgingly accepting the medium could no longer be avoided – and that someone of his growing status could benefit from its exposure (and income).

Yet over the next two decades he failed repeatedly to be – in one of his catchphrases from the BBC radio show Round The Horne – “properly serviced” by the small screen.

Despite all that graft on stage, he never landed a leading role in a TV drama series. For all the comic virtuosity that poured out of him in the Carry On films and his radio series with Tony Hancock and Kenneth Horne, he not once played lead in a TV sitcom. His stints as compere of BBC2’s International Cabaret from 1966-68 and again in 1974 almost gifted him a career as a TV frontman, where personal chat and camp indiscretion were elevated to equal importance with ritual pleasantry. Almost, but not quite: the format fell out of favour and these were not transferable skills Williams seemed able – or wanted – to redeploy.

Even during the 1970s, when TV guest appearances began to stack up and match his ubiquity on film and radio, he never came to be identified with a single television programme above all others that best radiated his gifts. There was only one TV series to bear his name, a mix of stand-up and sketch revue called The Kenneth Williams Show on BBC1 in 1970. It flopped so badly that he fled the country.

Come the end of the decade, however, he found himself embarking on a relationship with the small screen that, while gallant at best and tempestuous at worst, pretty much sustained the concluding part of his career.

The story of those final years is as much about a man being on television as a man writing about being on television. Williams’ diaries are still, to this day, an account of the business of making TV programmes unsurpassed in the level of detail and the quantity of self-criticism.

Other celebrity diaries are out there, itemising intrigue and mayhem across careers that match Williams in longevity. Other accounts of working in television are also out there, matching Williams’ fondness for indiscretion and score-settling. But none are as forensic or roam so widely across channels and formats. And none chronicle in such unsparing fashion who said what to whom before, during and after recording, regardless of how mundane or hurtful.

Williams could be haughty in public towards television and furious in private about its practitioners. Yet he surrendered himself time and again to the camera lens. Why? Yes, it paid well. But it also manifested, often simultaneously, the grandiose and the trivial: two adjectives close to his heart.

He writes in his 1971 diary of going to the BBC Television Theatre in Shepherd’s Bush and being “suddenly plunged back into that other atmosphere of illusion, lights, razzmatazz and rubbish. It was marvellous.” Though he gained a reputation within the industry for petulance and unpredictability, the industry kept asking him back, aware that if they got him on a good night, he was the best in the business.

Williams himself never owned a television set and steered clear of its social circles, branding them in his 1952 diary as “millions of ants, swarming all over the body of the theatre”. Yet he too kept going back. Thank heavens he did.

*

The new decade is only a few weeks old and Kenneth Williams has already been on television twice.

He has tried and failed to win a cost-of-living quiz on the Thames Television consumer show Money-Go-Round (“All these figures are rigged!”) and has been interviewed in Manchester by Shelly Rohde on Granada’s Live From Two.

In the weeks that follow, he’ll travel to Maidstone for the Southern Television discussion show Opinions Unlimited; to Birmingham for BBC1’s music-and-chat soiree Saturday Night at the Mill; make a return trip to Live From Two in Manchester; visit the BBC’s London studios at Ealing to tape Jackanory and Lime Grove for a spot on Nationwide; and pop up in Bristol on HTV’s Report West and in Norfolk on the BBC’s Look East while on a book signing tour.

1980 found Williams increasingly sporting the garb of a full-time TV star: a ritzy and well-suited look, despite his reservations. It was a look worn out of necessity as well as choice, however.

The start of the decade marks a dividing line in his professional life. Williams’ long film and theatre career had just come to an end. This can’t have been obvious to him at the time, but it must have hardened into reality as the months went by and offers of further work were either unforthcoming or too unappealing to accept.

Williams’ last appearance on film was in November 1978, in Carry On Emmanuelle, while his stage career concluded in January 1980 (“the prison sentence is over” he told his diary) with the final performance of Trevor Baxter’s play The Undertaking.

He would later spin this double-goodbye as a calculated rejection by himself of the cinema and the stage, one that aligned neatly with the trajectory of his final years. But with regular radio appearances now limited to Just a Minute, television was the one medium in 1980 where doors were still opening, not closing.

The door that required least effort from Williams to prop open was the one labelled ‘chat show’. This portal was one through which he had popped his head periodically since the mid-1960s, but which he’d started to enjoy traversing only in the early 1970s: the exact point in time, no coincidence surely, when he seems to have found a style of performance on television that was comfortable for him and which produced a reciprocal comforting response from host and audience.

This style was based partly on his persona on International Cabaret: a warmly enjoyable stew of camp, spite and self-deprecation that became a hit with a public hitherto unfamiliar with this version of Kenneth Williams. Here’s an example of one of his monologues, from an edition broadcast on 6 September 1966:

I was standing there in my peignoir, looking like an advert for soft furnishings. I went into the producer and said: ‘Here, Stu, me stuff’s gone! The suit’s gone! It’s vanished!’… He said, ‘You don’t know the half of it. Only last week I lost 48 Christmas trees in the middle of July’. I said: ‘Yes, well that’s all very seasonal, ducky, but that doesn’t help me. I can’t stand around here in my peignoir. People will start talking!’ Because that’s true, you know. Only last week I swallowed this pickled onion, and there were rumours. He said, ‘Well what do you expect me to do?’ I said ‘Get on to the insurance, put in a claim.’ He said: ‘I can’t, you’re not fully covered.’ I said, ‘I’m quite aware of that!’

International Cabaret, BBC2, 6 September 1966

Away from International Cabaret, with its particular demands and limitations, Williams’ style of performance on television grew in confidence and impact the more space he was given to develop and to display his armoury of skills, whether as an erudite witticist, a peddler of outrageousness, or as a walking anthology of anecdotes.

The first person to really give him this space – and to recognise the mutual benefits of conceding it – was Michael Parkinson.

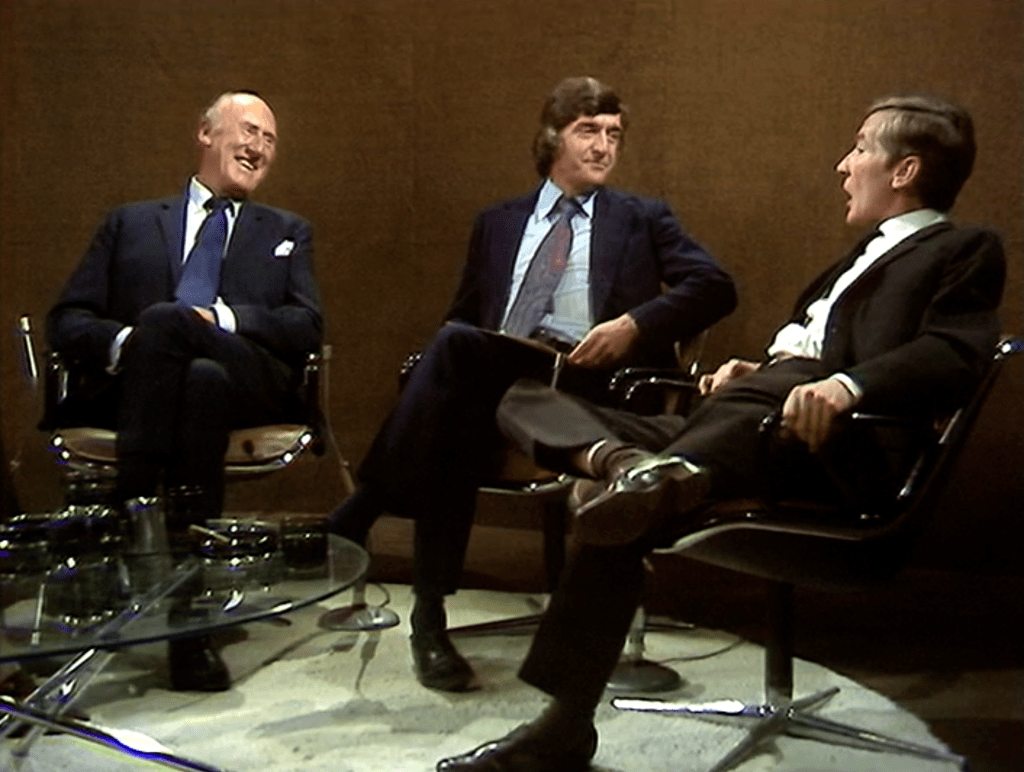

Williams’ debut on BBC1’s Parkinson show on 2 December 1972 coincided with a brief upturn in fortunes on the stage, coming after a hit play and occurring just ahead of another. He was suddenly the talk of theatre-world once more. A turn on a chat show, Williams may have reasoned, could now feel more veneration than evisceration.

So it proved. Footage of his appearance finds him looking relaxed in Parkinson’s softly-furnished chat nook, jacket open, one arm over the back of his seat, albeit dressed for a funeral. All eyes are on him. All ears too. He sits across from fellow guests Frank Muir and Patrick Campbell, but though all three receive equal billing, only one emerges triumphant.

Parkinson, BBC1, 2 December 1972

Williams utterly dominates the conversation, treating his host, guests and the studio audience to a dazzling sonata of observations, accents and impersonations. A long monologue on the “generosity of vowels” manages somehow to be both illuminating and hilarious. He is the last guest of the night and frankly, where else could he have been placed: he is the obvious finale, a literal show-stopper, leaving the previous acts – supports, frankly – looking on in awe.

Williams seems to have been thrilled with the reception to this appearance and also with Parkinson’s behaviour, who allowed space for Williams to develop a story, but who patrolled the boundaries of that space with diligence and gentle authority. No mean feat for two people whose off-screen relationship remained frosty for some time (Williams writes as late as 1974 that he “loathes” Parkinson: Parkinson recalled in 1995 of Williams: “At first, I couldn’t stand him”).

On-screen, however, theirs was a relationship that catalysed Williams’ thorough remaking as a television star. The incarnation of Williams on display here – conversationalist not agitator, a purveyor of tall tales, semi-grotesque impersonations and playful antagonism – would become the dominant one in the mind of much of the public for the rest of his career. And it was one the public enjoyed.

Only three other people really managed to establish the same kind of rapport with Williams on screen: Russell Harty and Mavis Nicholson in the 1970s and, much later in the 1980s, Terry Wogan.

All shared Parkinson’s skill of knowing when verbally to advance and when to retreat when sitting across from Williams in a studio. The bond with Parkinson was such a mutually fruitful one that by 1980 Williams was making annual visits to the show and thought nothing of spinning stories out for as long as Parkinson would let him. During his 1981 appearance he spoke about his army days uninterrupted for a whole five and a half minutes.

The following year Parkinson would turn his back on chat shows – or “talk shows”, as he pedantically referred to them – for his ill-fated involvement with TV-am, terminating brusquely one of Williams’ most enjoyable gigs. Williams was the natural choice for a guest on Parkinson’s farewell to the BBC on 3 April 1982, making his eighth visit (10th if you include two spots on Parkinson’s concurrent Australian series).

The end of such a fruitful and constructive means of employment might have tipped Williams into another of his intermittent crises of professional confidence, had he not, by this point in the 1980s, already begun to relax his self-imposed abstention from other genre staples of the small screen.

*

The change was most obvious in his attitude towards the panel game.

This was a format with which, until the late 1970s, Williams attempted only a fleeting association. But from the start of the 1980s through to the very end of his life, panel games – almost all of them on ITV – rampaged around the borders of his career like a brood of tenacious brambles, forever lurking in the corners of both his itinerary and his diary entries. The sparing attitude he had exercised towards these programmes during the 1970s evaporated and, as the 1980s went on and other income streams dried up, the threshold was lowered dramatically.

Once again, statistics help frame the story. Between 1980 and 1988 Williams made 14 appearances on Whose Baby?; 12 appearances on Give Us a Clue; five appearances on Through the Keyhole; was a guest on Looks Familiar four times; Child’s Play three times; All Star Secrets three times; Cross Wits twice; Password twice; The Pyramid Game once; and The Theatre Quiz once.

No panel seemed too lowly to grace, no game too frivolous, no request too trivial. Such engagements kept him in the public eye while keeping him in pocket, and in turn programme-makers kept hiring him, willing to reconcile his irascibility with his availability. His diary account of an edition of Child’s Play in September 1985 illustrates how the very act of his turning up for a recording had itself, by now, become a performance:

On stage with the audience I started more shouting and bawling and when I asked [Michael] Aspel, ‘When does this show start?’ he said ‘When you shut your mouth!’ which got a huge laugh and left me with egg all over the face.

His ubiquity on these shows became almost a running joke within the industry. Denis Norden introduced him on an edition of All Star Secrets in February 1982 as “The John McEnroe of panel games”. During a recording of Whose Baby? in October 1985, Williams records fellow panellist Nanette Newman as telling him: “We’ve been on these game shows, you and I, for years and years, haven’t we?” “Yes,” Williams replies, “and one day you’ll come and say, ‘Where is Kenneth?’ and they’ll say ‘He is dead’ and you’ll have to do it with someone else.’”

Whose Baby?, ITV, 18 July 1985

Williams and Newman first appeared together on a panel game in the BBC’s 1973/4 revival of What’s My Line? and their shared disposition towards accepting requests from TV producers meant they crossed paths several times, not exclusively on quiz shows: February 1986 saw them paired for a cookery spot on TV-am in which they prepared aubergines (“We’ve done a lot of things together but never cooking, have we Kenneth?” “I’m interested in the vegetarian stuff – it looks very good.” “Kenneth, I’ll cook for you any time!”).

He cared enough to want the panel games he cared about to be a success, confiding to his diary in January 1982 his unhappiness at not being chosen for a TV version of the BBC radio quiz Does the Team Think? (“It is a format well suited to me and could provide exactly the sort of series I’d be good in”). Over time, he grew to love some of them. In April 1981 he despaired of “the utter boredom” of Give Us a Clue; by June 1987 he sang of how “no show could be more enjoyable, ‘cos the people are all delightful to be with.”

As for the business of actually playing these games, scoring points or even – gasp – winning them, Williams was frankly a bit rubbish. This element of the panel game format meant having to perform on other people’s terms, in tightly-patrolled contexts: not his cup of tea at all. Consequently he often looked distracted, at sea, at his wit’s end, or just completely disengaged.

Most of the time it didn’t matter, however, as other panellists would come to his aid, or sense they needed to do the work and let Williams be Williams in the parts of the show when games weren’t being played. Anything that involved guessing the identity of people – Through the Keyhole, Whose Baby? – was pretty much beyond him. On Give Us a Clue he rarely joined in the work of guessing the mime, instead saving himself for the moment when he stepped down into the carpeted mini-arena to mime for himself.

Give Us a Clue, ITV, 31 December 1981 & 11 May 1982

One booking that should have worked on paper but never quite worked in reality was Williams’ 48-edition stint in 1982-83 in ‘Dictionary Corner’ on Channel 4’s Countdown.

He was only the second ever guest to perform this duty – picking up the mantle from where it had been indifferently tossed by Ted Moult – and could have exploited the show’s tottering infancy to make this role a real hit, elevating his own status in the bargain.

But this was years before Countdown had itself become a hit, with a devoted public following to boot. The sparse and restrained studio audience of these early months instead responded limply to the poised anecdotes Williams was required to discharge, while the programme-makers seemed unsure how to accommodate his persona.

The edition broadcast on 9 June 1983 – some way into Williams’ tenure – finds him talking at cross-purposes with host Richard Whiteley, doing funny voices to no response from those present, making a joke about Brussels sprouts that elicits about two laughs, and delivering an energetic spiel before the commercial break about the derivation of the words “vanguard” “caravan” and “dilly-dally”, to complete silence.

It’s tempting to think that had Williams appeared on the programme a few years later, when Countdown had fully found both its niche and its audience, and when Williams had fully graduated to the rank of elder statesman of TV comedy, the match would have been more fruitful for all concerned.

Countdown, Channel 4, 9 June 1983

*

In 1982 and ’83 this rank was still not quite secured. But Williams’ appearances on the small screen were becoming more frequent and he was leaving further behind all associations with being a working actor of stage and cinema.

It’s striking that not once during this period of increasing exposure was there an attempt to custom-build a TV series around Williams. Did the failure of his eponymous 1970 show still rankle after all this time, both for him and those in the industry? Or had all parties now realised implicitly that Kenneth Williams was not best on television when leading a revue of character-based comedy, and instead excelled as a) himself, in b) limited, concentrated doses, ideally leavened with c) other presenters or guests?

The latter was certainly in evidence as the decade continued and Williams’ guest spots moved beyond the world of the panel game and interviewer’s chair.

He just about survived an appearance on a special edition of Tomorrow’s World on BBC1 in January 1981, where he donned a tracksuit to demonstrate futuristic keep-fit apparatus, then joined fellow guests Diane Keen and Patrick Moore for a dinner party of synthetic foods. “Goodness, look at all those microamps I’m generating!” he cried, while trying on a wristwatch powered by body heat. “Think what you could do if these things were stuck all over you!” With space to perform, both solo and in concert with a small group of others, he was in his element.

By contrast, a turn on The Paul Daniels Magic Christmas Show on BBC1 in December 1982 was nothing but bother. Williams was first kept waiting in the studio for hours, about which he became increasingly vocally indignant. He then spent most of the recording sat on the side of the set looking like a spare part.

When the time finally came for his segment with Daniels, Williams seems to be near breaking point. “About time, I can tell you,” he spits. “I’ve been hanging about, watching a load of old rubbish”. “No one could argue,” Daniels replies charitably. He is then made to wear an enormous pirate hat. “What about my hair?” Williams complains, only half-joking. Daniels also puts on a hat, adding, “Now there are two of us that look stupid.” “Hmm,” Williams murmurs.

All of this is kept in the programme. Williams softens a little once the trick is under way and he is given a job to do – reciting swashbuckling prose – while Daniels does rudimentary magic with flags. But during a later break in recording, Daniels apparently confronted Williams, saying: “All you have done is moan ever since you came here.” “That’s right,” Williams retorted. “If you’d engaged extras instead of actors you wouldn’t have any trouble at all.” He told his diary later: “I would never work with this man again.”

The Paul Daniels Magic Christmas Show, BBC1, 25 December 1982

This kind of truculence never seemed to keep him off screens for long. His behaviour was possibly indulged more as eccentricity not malice, and his advancing years conferred harmlessness on the sort of antics which, if tried by younger artists, would probably have been professionally terminal.

The guest spots that were hand-tooled for him, where he was required to turn up and be ‘Kenneth Williams’ for only a few minutes, passed off more smoothly. These included singing the praises of Barbara Windsor in an edition of the BBC2 documentary series Fame in September 1981; talking to Central TV presenter Sue Jay about his religious beliefs in the late-night programme Come Close in April 1982; chatting with Sally James about keeping a diary on the BBC2 entertainment show 6.55 Special in July; dispensing comedy tips to Paul Heiney in an edition of BBC1’s In At the Deep End in September; and contributing his memories of Joe Orton to an edition of BBC2’s Arena in November.

His legacy also began to be valued just as highly as his act. Back in 1975 he had appeared in the BBC1 arts magazine Going Places, talking about his youth in the St Pancras district of London while leading viewers around “lovely rows of Georgian houses” and moaning about the “bed and breakfast vulgarity” of recent redevelopments. It was his first ‘authored’ piece of television and eight years later he was to retread much the same ground – literally – for a 30-minute episode of the BBC1 programme Comic Roots.

This was a series in which comedians and performers traced their childhood and early career by revisiting formative locations and old haunts. Though Williams hated the filming – a “ghastly self-devouring project” – the finished programme is a rich mix of fun and reflection, as well as being a priceless snapshot of Camden and Bloomsbury in the 1980s, when much of the area was still unchanged from the 1930s and ‘40s.

Williams is on fine form throughout, whether scurrying round childhood haunts recalling his mum’s put-downs of local characters (“…face like a bum with a couple of currants stuck in for eyes…”), singing and japing with locals in a pub, or – to use one of his favourite phrases – revolving memories about his younger days. There is even a rare glimpse of Williams in a theatre, albeit an empty one, as he stands on the deserted stage of the Lyric Hammersmith and offers some parting words:

Performing is making an act of faith, believing that you can create reciprocity between the auditorium and the stage. And that’s why, when the atheist says, what if life’s pointless, what if it’s all a joke, it has to be answered by the comedian: well, if it is a joke, let’s make it a good one.

Comic Roots, BBC1, 2 September 1983

The programme caught the attention of the broadsheets, who by now had started to treat Williams as more of a thoughtful curiosity than a brash jester. Here’s Peter Ackroyd in The Times:

How else can you rise above the size, dirt and anonymity of the great city except by being outrageous… He is a most engaging man – he lives in a world of comic fantasy, in which he is the only inhabitant.

Mick Brown in The Guardian offered a persuasive explanation for the appeal and distinctiveness of Williams’ brand of humour:

Sown in postwar British radio, flowering in Carry On and now dried and tempered into an erudite and waspish line in anecdote, [it] has always seemed so particular to Williams as to have no obvious antecedents.

If anyone needed further evidence of Williams’ ability to hold an audience spellbound with exactly this kind of humour, it came just a few months later in the shape of An Audience With Kenneth Williams.

Easily his most virtuoso solo television appearance, this was an eye-opener to anyone not yet familiar with his command of a lengthy anecdote or tall tale. Taped by London Weekend Television in December 1982 but left on the shelf for a year before being indecently buried on Channel 4 at 10.25pm on December 23 1983, it deserved a better slot. Yes, it was almost 90 minutes long, but Williams never flagged, helped hugely by the sympathetic celebrity audience who were happy to overlook his occasionally frenetic delivery, and by sensitive production from Richard Drewett, whose association with Williams went all the way back to 1972 when he had booked him for Parkinson.

With all boxes ticked – army hijinks in Singapore, theatrical brushes with Edith Evans and Orson Welles, behind-the-scenes on the Carry Ons, favourite put-downs, reflections on the art of humour, a couple of sung party pieces – it remains the most precious document of Williams’ latterday iteration as the nation’s vivacious if squally raconteur-in-chief.

*

1983 also saw Kenneth Williams embrace a new type of UK broadcasting, which would provide a further outlet for his talents over the next few years: breakfast television.

Living in the centre of London meant it took only 15 minutes or so for Williams to travel to all the main TV studios in the capital: London Weekend Television on the South Bank; Thames Television on Euston Road; and BBC Television Centre in Shepherd’s Bush. To this list were added, from early 1983, the BBC Breakfast Time studio at Lime Grove near TV Centre, and TV-am’s headquarters in Camden.

From the outset, Williams seemed entirely at ease with breakfast television’s eclectic and unfussy attitude to celebrity bookings. A lifelong early riser, he had no trouble performing as early as 6.30am and seems to have struck up an easy and fruitful relationship with both of the rival services.

He first appeared on TV-am on 22 February 1983, just three weeks after its launch. The station was already flailing in what would become, over the next few years, a near-constant stream of financial calamity and undignified personnel spats. But Williams seemed utterly unaffected, chatting with David Frost about his 57th birthday – which was that very day – before exchanging pleasantries with Anna Ford and Angela Rippon.

Williams would grace TV-am’s economy-beige sofa on a total of 22 occasions between 1983 and 1987: 12 times as a guest and 10 times to review the week’s newspapers. The paper reviews were mostly pre-recorded on a Saturday for transmission the following morning, so by necessity focused on non-topical articles or items from journals, and paired Williams with the likes of John Wells, Nigel Rees or Derek Jameson.

More freewheeling – and hence more entertaining – were the guest spots: live, sometimes as sole guest, sometimes with others, sometimes involving an activity, such as preparing those aubergines with Nanette Newman or making a pancake with Rustie Lee (“I really should have an apron on… I don’t mind breaking an egg or two, but I hope I haven’t got to actually toss it, because I’m no good at tossing!”).

He seemed always to enjoy these trips to Camden Lock, comfortable both alone or swapping tips with Dora Bryan about how best to empty a vacuum cleaner, reminiscing about the war with Jimmy Edwards and Tommy Trinder, and – quite the turn-up – bonding with someone embodying the absolute opposite deportment to himself, Bernard Manning, over a shared admiration of the music-hall comedian Jimmy James.

Good Morning Britain, TV-am, 3 March 1984 & 23 July 1985

He never appeared with Michael Parkinson during the latter’s brief and unhappy association with TV-am; perhaps neither wanted to invite comparison with their BBC partnership. He nonetheless got on well with the hosts of both breakfast television services, whether being lightly grilled – the obligatory phrase for this time of day – by Anne Diamond and Nick Owen on ITV or by Selina Scott and Frank Bough on BBC1.

He made fewer appearances on Breakfast Time than TV-am – five in total – but they were just as successful, both for Williams personally, showing him at his most easygoing and affable, and for the programme itself, Williams pitching himself at just the right level for the show’s unique confected atmosphere of relaxed conversation and passing glances at topicality.

His first Breakfast Time on 11 August 1983 found him on hand for almost the entire broadcast, popping up periodically to chat about the Carry Ons, the war, the forthcoming Comic Roots and to answer viewers’ questions. Subsequent appearances saw him trek verbally across topics as diverse as his mother, holidays, the bombing of Hiroshima and the christening of his godson.

There was something about the camaraderie of both breakfast TV operations that clearly struck a harmonious chord for him, with their respective teams of friendly faces and production staff operating slightly on the fringes of mainstream television and espousing a warm unconventionality. “They were all very pleasant to me,” he wrote in his diary of TV-am, while Breakfast Time had a “smashing team… Frank Bough said ‘Thank you! You’re a prince.’”

Magazine formats of other kinds provided further TV work for Williams during this period. It probably helped that they were different enough from chat shows and panel games for him to feel he was spreading his talents, rather than rely wholly on the same types of employment.

Viewers in London saw Williams make six appearances on LWT’s regional Friday teatime fixture The Six O’Clock Show between 1984 and 1987. The benefit of his proximity to LWT’s South Bank studios was illustrated vividly on 21 February 1986, a turbulent day according to his diary, much of which had been spent coping with a nasty fall his mother had suffered in her neighbouring flat. Williams was occupied for most of the morning and afternoon attempting to find a hospital to admit his mother, with an ambulance arriving only at 4.50pm. He then “quickly changed into a suit”, hurried down to LWT for 6pm, chatted about his impending 60th birthday with host Michael Aspel and co-host Danny Baker, and was back home by 7.10pm.

Williams’ dedication to this kind of frankly low-grade appearance was laudable; others with less commitment would surely have pulled out, citing a family emergency. His fondness for this show, and particularly Baker – not so much Aspel – was probably an additional factor.

Williams leant his name to three books during this period: Acid Drops (1980), a collection of societal retorts and public witticisms collated by Gyles Brandreth, for which Williams provided a foreword; Back Drops (1983), a reworking by Brandreth and Clive Dickinson of Williams’ 1981 private diary, augmented with jokes and semi-fictional encounters; and Just Williams (1985), his autobiography up to 1975 – the year before he turned 50 – again co-written with Brandreth.

Each publication gave TV programmes, particularly magazine shows, a fresh reason to have Williams as a guest. Bookings duly came from the likes of Nationwide and Pebble Mill at One as well as regional magazines Look North (BBC1), Look East (BBC1) and Report West (HTV). Regional discussion shows also came knocking: Opinions Unlimited (Southern Television), After Hours (Thames), Friday Night (Granada), Sunday Best (Yorkshire), Daytime (Thames again) and Live From Two (Granada again).

These appearances could be quite hairy, with Williams’ attempts to be more of a sage than a gossip not always successful within the slimline format and brief running time. His spot on Opinions Unlimited in May 1980 left him fuming when his contribution was cut short to make way for a debate on whether men should wear white or coloured underpants. He considered his contribution to After Hours in December 1983 “useless”, believing Mavis Nicholson had let a discussion about censorship ramble off topic.

His appearance on Daytime in January 1985 was as a contributor to an audience discussion about the EEC: a responsibility Williams took seriously enough to ring up the Department for Trade and Industry to arm himself with facts and figures. Overcoming host Sarah Kennedy’s insistence on referring to him as the “archetypal British gent”, Williams stoutly defended the Common Market (“Idiosyncratic things will always exist within communities… The benefit from it is enormous. We’re in it for good”), though footage suggests both Kennedy and the rest of the small studio audience were waiting for jokes and funny voices, and there is an air of disappointment when they don’t arrive.

His stints on discussion shows could also affected by the disposition of his fellow participants. The wrong blend of guests – people who didn’t really understand or appreciate what Williams was there to offer – could prove calamitous.

An edition of the BBC1 moral discussion show Choices in May 1982 almost went off the rails thanks to a personality clash between Williams and fellow guest Labour MP Philip Whitehead. Following a lengthy response from Williams, Whitehead made what he presumably intended to be a light-hearted remark about “getting a word in” after “this megastar”. Williams bridled silently but remained composed, then exploded after the recording in a rant he took great pains to record in his diary, accusing the MP of “sneering cracks” and making “derisive” remarks. “I shouted so much at the man, he was quite shaken; my anger was appalling… I wrote a note apologising for the outburst, not for the complaint, but for the form it took.”

An appearance on the BBC’s One O’Clock News in June 1987 found him alongside Eleanor Bron and Robert Powell to discuss who they each thought should win the impending general election. Perhaps reacting to his colleagues’ reticence and less than articulate responses, Williams over-compensated and let fly with a rather hectoring endorsement of the Conservatives, dropping in references to Marks & Spencer and the theatrical promoter Binkie Beaumont, before ending with a garbled tribute to the-then foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe, a man who “doesn’t reveal the ontological profundities of which he is capable”.

More successful, by virtue of being in a calmer and more supportive environment, was an appearance in June 1984 on BBC2’s Private Lives. This was a self-consciously alternative format for a discussion show, devised by its host, the actor Maria Aitken, and structured around guests responding to Aitken’s shopping list of anecdotes: earliest memory, thoughts on travelling, a precious object, a favourite piece of music. “I usually find that the water affects me,” Williams began on the subject of travel, “I do have the most appalling problems…”, by which point the laughter was already flowing, from Aitken, fellow guest Germaine Greer and the studio audience. “If you’re gonna go from A to B you obviously want to get to B – you don’t want to linger in between. That’s ludicrous!”

He chose as his favourite object a miniature whale given to him by Orson Welles during their time in Welles’ stage adaptation of Moby Dick, while his favourite piece of music was the Neapolitan aria Torna a Surriento (Come Back to Sorrento), which he recalled watching David Whitfield sing in South East Asia during the war. When the song was performed live in the studio, by tenor Robert White accompanied by Peter Skellern on piano, the camera focuses on Williams, who sits transfixed: a moment of complete stillness that nonetheless speaks volumes.

Private Lives, BBC2, 12 June 1984

Having guests on hand who Williams respected without qualification was an even greater boon. One of his last appearances on television was in November 1987 on the BBC2 book discussion programme Cover to Cover, where he took great delight in getting to share a studio with the American novelist Patricia Highsmith – and an even greater delight in recording how she greeted him: “You are Kenneth Williams? I so wanted to meet you.”

*

Only one genre of television threaded its way comfortably throughout Kenneth Williams’ entire career on the small screen: children’s programmes.

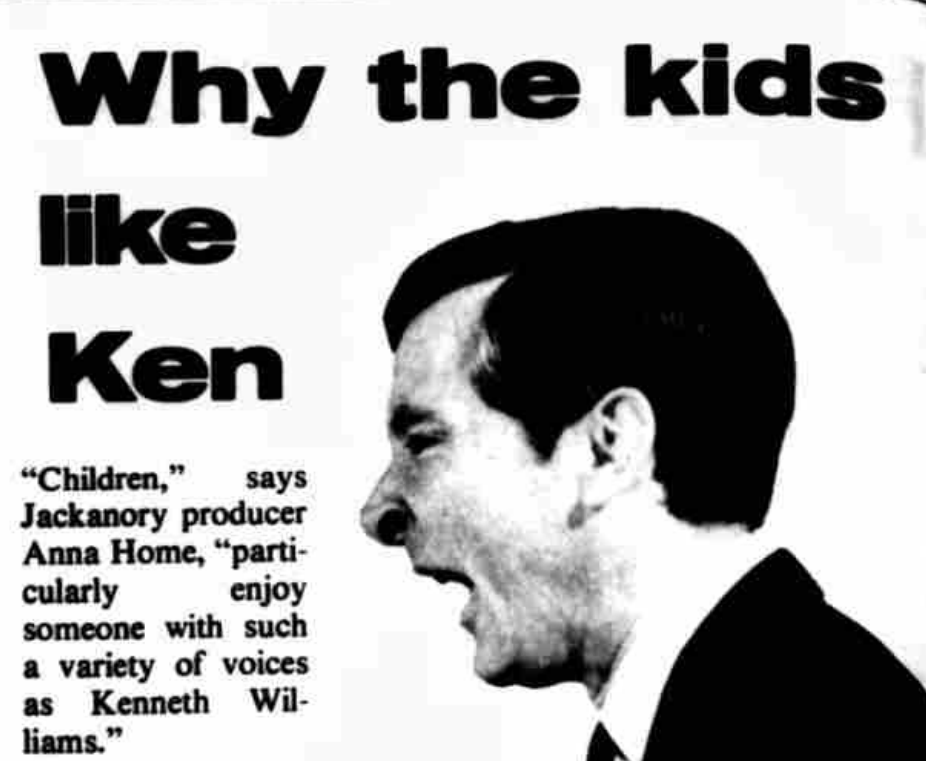

He made his first appearance on BBC1’s Jackanory in 1968 and made his last in 1986, clocking up a total of 12 weeks’ worth of tales, plus two stints co-hosting the show’s writing competition. Nobody was more prolific, save Bernard Cribbins (and there can be few more deserving of that accolade).

A publicity shot for Williams’ first Jackanory, The Land of Green Ginger, broadcast December 1968 (Television Today, 12 June 1969)

His diaries and other sources testify to a reciprocally warm, harmless and utterly uncynical relationship between himself and children. He loved their company and vice versa. This shone through his work on Jackanory. Williams found taping his first story, The Land of Green Ginger, “pure agony… trying to characterise loads of characters is like running a marathon. I collapsed exhausted into a taxi.” But he mastered the format quickly enough that by his second, The Founding of Evil Hold School in 1969, he was at the top of his game, Stanley Reynolds writing in The Guardian of how Williams was “marvellous doing the different voices and pulling his face around like putty to fit the speech”.

“Did you hear about the reaction?” Williams gushed in an interview that same year. “Great parcels of letters saying please bring back that good-looking, clever, witty young Kenneth Williams. And from kids you know there’s no flannel – it is an honest reaction.”

Anne Home, the show’s producer, said: “Many people thought he would not amuse children, but he has only to twitch his nose and they howl.” In 1970, viewers were asked to vote for stories they’d like to see repeated as part of a Jackanory Request Week; guess who came top.

(Harrow Observer & Gazette, 16 July 1971)

Williams always insisted he was not a physical comedian, preferring verbal humour and wordplay. Jackanory, which required its performers to sit almost perfectly still and rely chiefly on the voice, suited this side of him perfectly. It must also have helped him realise – and then refine -his flair for delivering dissertations on camera.

As far as audiences were concerned, Jackanory had the far more significant effect of introducing a whole new generation to the man, one not familiar principally with either his radio or film careers and who would in turn always associate him principally with TV.

Anyone growing up in the 1970s and early 80s quite possibly encountered Williams first on Jackanory, sitting usually in a high-backed chair wearing a dark jacket and big cravat or bow-tie, captivating and intriguing in equal measure with his by now well-polished armoury of voices and expressions.

Few had quite such a grasp as Williams of how the simple act of telling a story could enchant the young, particularly how tantalising it was to be told, at an episode’s conclusion: “The gloomy procession marched on, when suddenly… NO! I’ll tell you about that tomorrow. Goodbye!” (episode four of The Rose & the Ring, January 1975).

The appeal was compounded by his spots on the Jackanory Writing Competitions, where he showed nothing but the utmost respect for the thousands of entries, reading even the shortest of verses with the same care he would accord the work of a classical poet.

Jackanory, BBC1: The Rose & the Ring, 6 January 1975 (top left); The Dribblesome Teapots, 20 November 1978 (top right); Jackanory Writing Competition, 18 December 1978 (bottom left); James & the Giant Peach, 10 February 1986 (bottom right)

Williams’ success on Jackanory encouraged the BBC children’s department to try and deploy him elsewhere – with mixed results.

His talents were barely tapped in the pantomime-lite special Let’s Make a Musical in May 1977, where he joined other children’s TV faces in recreating the story and songs from the West End musical Pickwick. December of the same year found him again largely acting as background colour in an edition of The All-Star Record Breakers, though he did get to essay some splendid ribaldry with Roy Castle about the world’s largest saxophone (“I hope you’ve got plenty of puff! I used all mine up getting it up the stairs – and I’m one of the biggest puffs in the business!”).

When he appeared outside drama or storytelling formats, such as one of a team of fellow entertainers on the knockabout quiz Star Turn, or dropping by as a guest on Swap Shop, he sometimes came over more dour than mischievous; on the latter, his choice of items to swap with viewers was typically functional: a pair of gloves and a pencil.

It wasn’t until 1981 that the BBC hit bullseye, in the shape of Willo the Wisp. This collection of delightfully absurd and sly modern-day animated fairy stories had its origins in a 10-minute British Gas children’s educational film from 1975 called Super Natural Gas, which Williams had voiced. Animator Nick Spargo went on to develop the film’s character – a talking plume of marsh gas – into the titular gossipy spright, modelled on Williams’ own face. Spargo also wrote the scripts, with Willo spinning tales of comical and lugubrious misfortune involving an eccentric mob of talking creatures that lived in Doyley Woods.

The whole thing suited Williams down to the ground, exploiting to the full his conversational style of narration, his flair for comic voices and his fondness for doing a solo turn. Willo the Wisp was scheduled in autumn 1981 just before the early evening news on BBC1 (despite the BBC supposedly objecting, saying it would be “wrong” to have the likes of Williams filling the nation’s ears ahead of a bulletin) and its 26 episodes became a hit with children and adults alike.

Williams loved the material (“I admire Nick Spargo’s industry and inventiveness! His ideas are charming” he told his 1980 diary) but loved the reaction from the public even more. The show’s popularity was beyond question; even workmen in the street started hailing Williams with the cry, “Here’s old Willo the Wisp!” There was soon a mini-industry of promotional spin-offs, including long-playing records, storybooks and a 7” single called Down in the Woods, with Williams trilling lyrics to the song’s instrumental signature tune (“Down in the woods where it’s too dark to see/There’s a light dancing – and that light is me!”).

When he appeared on Blue Peter in October 1982 to talk about how he devised the voices, presenter Sarah Greene gave him a gift of a miniature model of one the characters, Arthur the Caterpillar. “That is really smashing!” he said, genuinely touched. “And he won’t talk unless I let him!”

Nothing else he did for children’s television, Jackanory aside, quite matched the impact of Willo. He made occasional appearances on ITV programmes for youngsters, gamely swapping corny jokes with Christopher Biggins in a couple of cameos on the TVS game show On Safari (September 1982 and July 1983), and answering questions with bubbly enthusiasm from an audience of kids on the Thames magazine CBTV (July 1982).

But he was never hired for a stint on ITV’s alternative to Jackanory, The Book Tower, a format ready-made for his storytelling talents. And the one children’s series for ITV in which he took a regular role seems to have almost broken him. This was Whizzkid’s Guide (1981), a comedy show by Southern Television based on the book The Whizzkid’s Handbook by Peter Eldin. Williams found himself playing both a teacher and a pupil in sketches of varying quality, alongside a motley collection of co-stars including Arthur Mullard, Sheila White, Patrick Newell and Rita Webb.

Such an assembly of ill-matched souls was almost bound to incur Williams’ wrath and so it proved; he fell out with almost all of them, Webb abusing him in earshot (according to his diary: “I’ll knock his fucking block off – he’s a cunt, spelled with a K”), with Williams eventually spending as much time as he could in his dressing room or eating meals in the canteen with the wardrobe staff. “Never has a television job proved so unpleasant, thankless and boring,” he concluded.

It was as if only the BBC knew best how to use and sustain Williams’ appeal to children. Certainly the corporation became adept at crafting roles around Williams, often in isolation, rather than try to crowbar him into an ill-fitting format alongside others. For a BBC pantomime on New Year’s Day 1984, Aladdin & the Forty Thieves, Williams was deliberately kept apart from the rest of the cast, his contribution – a short story told direct to camera – slotted into the show halfway through.

The following year Williams gave his voice to a splendidly acid-tongued computer in the sci-fi romp Galloping Galaxies, a role that – like Willo – didn’t require him to appear on screen at all. And, just like Willo, it worked, the mere sound of his vocals enough to give human personality to, in this instance, a piece of boggle-eyed machinery. In one episode a crew member taunts the computer, Sid, by asking “How can you run without legs?” To which Sid, aka Williams, replies tartly: “How can you think without a mind?”

*

Appearing in November 1973 on the LWT chat show Russell Harty Plus, Williams had kicked off proceedings by complaining about his studio chair: “Not PVC is it? I hope it’s not, it sticks to your bum, it’s dreadful. I’m sorry, I’ve realised it is real calf, isn’t it, it’s leather. You do yourselves well here!” In February 1984, more than 10 years later, he was once again hosted by Russell Harty, this time on BBC1 – and once again, business got under way with a gripe about the upholstery:

It’s certainly recherché this set. What a rotten design. A banquette is ludicrous. I mean, it’s practically calculated to give you curvature of the spine. How can you sit properly on a set like this? You’d think they’d have spent some money!

Eleven months later in January 1985, seating arrangements were still on his mind, telling the presenters of TV-am’s Good Morning Britain: “Your furniture ain’t changed here – very uncomfortable.” Settling gingerly into his seat on Joan Rivers: Can We Talk? on BBC2 in March 1986, out it came once more: “Thank God it’s not PVC I’m sitting on. I can’t stand that stuff, and I have to be very careful as you probably know – yes, I’ve been in three times for the operation.”

Russell Harty Plus, ITV, 2 November 1973 & Joan Rivers: Can We Talk?, BBC2, 24 March 1986

The same anecdotes, like the same obsessions, came to dominate Williams’ chat show appearances and guest spots in his final years. On at least four separate programmes in the 1980s he told a story about an author at a book-signing thinking a member of the public had asked for a dedication to “Emma Chisit”, when they’d actually said, “How much is it?” His Dame Edith Evans impression, first essayed on Parkinson in the 1970s and dusted down for An Audience With… (“This place has gone off terribly!”) was another favourite.

To this list was added the subject of Williams’ wellbeing. This had been of peripheral concern since the early 70s – he’d told Harty in 1973 “I’ve been on more traction beds than you’ve had hot dinners” – and even turned up in an edition of Give Us a Clue in May 1982 (“I’ve had the operation you know – it’s amazing I’m here at all; the surgeon said it’s like a patchwork quilt!”)

But it became a near-constant from the mid-80s onwards. Joan Rivers indulged it with flattery (“You’re wonderful!”). Anne Diamond seemed bemused on TV-am in January 1987 when Williams launched into a detailed description of having a “tube up the rear” for a barium enema. The following month he walked on to set of Aspel & Company and launched into a two-minute medical monologue before Michael Aspel had even opened his mouth, culminating in Williams recalling a doctor announcing:

“‘You have a spastic colon’ – as if I come into money!… In the old days, you were better off. Because nowadays they’re all specialists. Everyone’s becoming better and better at less and less, and eventually someone’s going to be superb at nothing!”

As a performance, it was a sight (and sound) to behold. But there was also something a little unsettling about Williams mining his apparent deteriorating health to such an extent, and it then receiving gales of laughter. The audience reaction was as much at how Williams was describing his plight – the screwed-up face, the shrieking vocal chords – as what he was saying.

The published diaries don’t reveal whether he tuned in two days later to watch the programme’s transmission. He seems to have had few qualms about watching himself when he could do so – typically on his mother’s television set in the flat next door – if only to find fault with his appearance.

“It was quite a shock to see my face… It looked scraggy and baggy-eyed,” he reflected on his turn on Parkinson in October 1979. He thought he appeared “very dried-up and prune-like” in the Fame documentary in September 1981. “I’ve not got the warm friendly face of a children’s presenter,” he concluded after sampling some of his October 1983 stint on Jackanory. “Oh, how old you look,” he wailed in February 1984, on catching sight of himself on the LWT show Sunday Sunday, “The hair very much whiter and the face lined and shrivelled.”

Yet he kept watching, just like he kept going in front of the camera. One probable reason he did so, despite concerns about his health or appearance, was the promise of a warm reception – from host, the public, or ideally both.

The presenter of Sunday Sunday, Gloria Hunniford, was very much in Williams’ pantheon of friendly faces; he made three trips to the show between 1983 and 1986. His first, in February 1983 to promote Back Drops, brought from Williams such a concentrated onslaught of hilarity – and such audible audience merriment – it reduced Hunniford to tears of joy.

Shelly Rohde, presenter of Granada’s Live From Two, was another excellent foil. She interviewed Williams twice in 1980, the second time giving as good as she got during a discussion on the meaning of eccentricity, which culminated in Williams musing on the link between homeopathy and fine dining. “Even though you say you’re not eccentric,” Rohde chided in good humour, “to have arrived at a conversation where we’re talking about health and oysters has to be eccentric!”

A guest spot on BBC1’s Saturday Night at the Mill in June 1980 was greeted by “deafening” applause, with “the audience so much on my side that I could do no wrong.” On this occasion Williams overruled the wishes of the production team and insisted on being interviewed by Bob Langley – another friendly face. There was no doubt his senior years now commanded more than just curiosity within the TV industry.

It led to several instances of stunt casting, however: producers and talent bookers hiring Williams for the sheer novelty of inserting him into unlikely situations or alongside unlikely co-stars.

Into this category must be placed his appearance on BBC1’s medical magazine show Bodymatters in September 1985, where he was required to emerge into the studio through one of the nostrils of a giant replica of his own nose; a turn on the BBC1 daytime debate show Day to Day in 1986 hosted by Robert Kilroy-Silk, where he dispensed bon mots on the subject of accents alongside Irish novelist Frank Delaney and comedy writer Johnny Speight; and an entire run of the Granada light entertainment oddity Some You Win in summer 1984.

This Saturday night seven-part series promised a “light-hearted look at life’s winners and losers”; it delivered a ragbag of celebrity interviews, songs and anecdotes, helmed by the implausible trio of Williams, Lulu and Ted Robbins. This was not Williams’ natural environment at all. It was painful to watch him serving up verbal fancies within the auspices of a shiny-floor ITV show, and to bop along with the audience as BA Robertson’s synth-pop signature tune played over the credits. “I’ve been sold a pup,” he winced to his diary. “I don’t really belong at all… it wants someone young-looking and energetic… and someone who wants to hear pop music.”

*

“This must be the last bloody chat show surely?” Williams wrote in March 1984, following an appearance on the Television South West programme Judi, hosted by Ms Spiers in front of “two rows of hard chairs to accommodate about 40 elderly Plymouth residents who looked vaguely discomforted.” Yet one final round of sofa-based employment was about to begin.

In the autumn of 1985, Williams received an invitation to appear on BBC1’s recently-launched thrice-weekly Wogan. Despite having hosted chat shows on the BBC since 1982 and become the network’s de facto replacement for Michael Parkinson, Terry Wogan had never properly interviewed Williams on television. Maybe Wogan was keen to avoid the suggestion he was relying too much on guests associated with his predecessor. Perhaps Williams felt residual loyalty to Parkinson and didn’t fancy having to strike up bonds with a new interrogator. Maybe the call never came or the request was never answered.

Whatever the reason, by 1985 enough time had seemingly passed for the Wogan production team to make the offer and for Williams to accept. For both parties, it was a wise move. Williams would make a total of eight appearances on Wogan between September 1985 and December 1987, plus a further three as guest host. Whatever reservations Williams may have had about frequenting another “bloody chat show”, these were evidently sufficiently calmed, or at least mollified, to launch a relationship that rewarded him with some of the biggest TV audiences of his career.

His first appearance was on 13 September 1985 and he seemed instantly at home. He talked freely about the Carry Ons, related an anecdote about Richard Burton that lasted a full two minutes without interruption, before settling on the now-inevitable topic of his health – specifically a recent operation on his “nether regions… They shave everything – oh, it’s dreadful, and you feel afterwards as if a porcupine is down there!” Wogan’s response was spot on, alternating between the attitude of a GP listening to a patient and a kindly cardinal hearing confession.

Williams was asked back just seven weeks later, then again for Wogan’s live 1985 New Year’s Eve show. Perched on a voluminous sofa (about which he voiced no complaint), he was joined by Ronnie Corbett, David Jason and Julie Walters. Full marks to the guest booker for a properly class line-up.

Wogan, BBC1, 31 December 1985

Williams appeared relaxed, joking and chatting among friends, happy to toast the arrival of the new year with balloons and a glass of fake champagne. His memories of 1985? Getting a fishbone stuck in his throat at a literary function and being praised for his efforts as the voice of the Bloo Loo toilet cleaner. His resolution for 1986? “I’m going to eschew modesty and blow my own trumpet!”

As the months went by and the repeat invitations kept coming, Wogan’s producers, faced with a format that gobbled up around 15 guests a week, may well have resorted to Williams more out of necessity than choice.

But the fact he remained first on the list when it came to last-minute bookings meant at the very least his twilight years weren’t spent in obscurity. As it turned out, it also gave the country numerous last chances to see the man in action, and for his elder-statesman period to preserved generously on tape.

The most generous occasion of the lot came in April 1986, when Williams was asked to take over the role of host for three shows while Wogan was on holiday. It had been more than 10 years since Williams had last fronted entertainment on television, as compere of International Cabaret, while interviewing others was something he had never done before.

But the show’s producers – Frances Whitaker and Peter Estall – had worked on the Private Lives series, so had seen first hand Williams’s ability to deploy, at length, bursts of comedy and insight. And Estall quickly struck up a solid working relationship with Williams, using the correct mix of flattery and authority to keep his star both respected and reassured.

Although Williams found the assignment at times uncomfortable – “I’ve never worked in such confusion!” – particularly when guests dropped out and material ran short, it didn’t show on screen. Williams stood revealed as not merely a charming gossip (“The producer said, ‘Let them see the uninhibited Kenneth! Let it all hang out!’ I thought hello, sounds like a naturist’s paradise”) but also a sharp, fluent questioner.

He listened with attentiveness and was served wisely with guests with whom he already had a friendship – Derek Nimmo, Nicholas Parsons, Barbara Windsor – or who came armed with plenty to say – Stephen Fry, Michael Palin and Janet Brown.

He wasn’t as restrained as Wogan, Nimmo ordering him at one point to “be quiet – he just keeps on chatting”. Neither did he have the ability to make all his guests feel completely at ease, with actor Fay Masterson looking particularly nervous.

But the fact he wasn’t Wogan, or even a carbon copy of Wogan, was partly the point. And the audience were treated to something they never got from their usual host: comic monologues, peppered with jokes Williams had dusted down from his time on International Cabaret, and delivered with an energy that belied his years:

When I arrived here tonight I was besieged – the fans! I had to remonstrate, I said here, you two ladies can be heard halfway up the street! This is a BBC show, people are trying to sleep… They said there’s a running buffet. I ran, I nearly caught up with it twice.

He carried on even when the show had gone off air, telling the audience after his first night:

You were a very good house, not terribly intelligent, but there we are. And this show being live means we’re all under a great deal of stress and tension – I find when I walk off, I may look cool and calm, but I don’t collect much, I can tell you that – not with the BBC!

Post-transmission of Wogan, BBC1, 21 April 1986

He opened his final show as host with mock-protest (“The producer said, ‘You’ve got the elbow, they’re laying you off’. I said, I’ve hardly been laid on!”) and closed with a reworked song from his Round the Horne character Rambling Syd Rumpo (“Oh they asked him up to London to do Wogan for a week/But he trod on his cordwangle and was up before the beak!”).

He then led the entire audience in a rousing rendition of My Bonnie Lies Over The Ocean, the chorus changed to “Bring back, bring back, bring back Terry Wogan to me!”

Wogan, BBC1, 25 April 1986

Had Williams been offered his own chat show as a result of these efforts – “Everyone seemed pleased,” he noted in his diary – it’s tempting to conclude it would have been a hit. But even if such an offer had been made, chances are Williams would have refused, citing any number of reasons (health, lack of material, indifference).

His attitude to work as he approached his seventh decade was summed up in an interview in the Guardian in 1984: “All I want to do is to earn enough to keep myself and provide for my old age and after that I’m really not interested.” As it was, Williams was not asked back for more stints in the Wogan chair. But the guest spots continued, and the last of these, on 30 December 1987, would also turn out to be his final appearance on BBC television.

Co-opted with Hugh Paddick into reprising their Round the Horne characters Julian and Sandy as part of a radio comedy special, it was not the most fitting send-off. Wogan was no Kenneth Horne and delivered his lines in a halting fashion. The audience reacted to Julian and Sandy’s trademark polari with a mixture of bemusement and cautious approval. “It was a regular omi from omi,” Williams shouted at one point, to near-silence from the studio. Even a retread for one of the best jokes from the original series fell flat (“Did you manage to drag yourself up on board?” “No, just casual wear, jeans and sweaters…”).

Before the recording Williams wrote in his diary of how he wished he’d “never agreed to do this sketch… the subject of homosexuality is now in great disfavour. When we were performing the Jule and Sand stuff in the 60s the atmosphere was utterly different, and of course, nobody knew about Aids.” His misgivings were proved right. Tastes had changed, along with prejudices. The sketch fizzled out with a chorus of The Lambeth Walk. The audience applauded on cue, but without joy. As quickly as he could manage, without bothering to even have his make-up removed, Williams left the Television Theatre and returned to the sanctuary of his flat, consoling himself with a tin of soup and two slices of bread.

*

An air of commemoration infused Kenneth Williams’ appearances on television long before what would prove to be his final spot on Wogan.

The chat shows and interviews of the 1980s had initiated the process, but it was accelerated by the way Williams became more and more famous principally for what he had already done, not what he was doing or might be about to do. Both guest and interviewer gave the impression, at least on screen, of being happy to go along with this. Yet in private Williams was troubled increasingly by what he regarded to be his transformation into an anecdote-dispensing automaton.

In 1985, at the outset of his association with the Wogan show, he wrote in typically unsparing language of how appearing on chat shows had reduced him to “eating at myself for years… just living off body fat… and people say ‘All he does now is go on and tell those old stories we’ve all heard before with his usual lavatory gags and his camp blether…’ Pathetic.” “Oh dear – I’m 60 and still trying to be funny,” he lamented during his stint hosting Wogan in April 1986. Of his 1987 appearance on Aspel & Company he conceded that while the “audience was super… of course I felt all the self-loathing after, over such appalling indulgence.”

Yet this was not the dominant impression conveyed to viewers at the time. Unless you made a point of catching every single appearance Williams made on TV, the stories always sounded new and alive, told by a man who was evidently of advanced years but not obviously of advanced unhappiness, and who still brimmed with fresh insight and wit.

It helped that Wogan, Aspel and others created around Williams a very generous and respectful aura, evocative of a harmless elderly relative popping round for tea and a chat about the old days.

For the young, meanwhile, Williams was still a welcome semi-permanent presence on television. He had appeared on Jackanory as recently as 1986, and his voice was still being heard in episodes of Galloping Galaxies in autumn 1987. He had not vanished from the nation’s sight or mind. Reminders of his faculties and his appeal were close at hand as 1988 began, thanks to a series of Carry On repeats on ITV and four appearances on Give Us a Clue, though these had been taped back in summer 1987.

So when Williams died a few months later, on 15 April 1988, there was no need to remind anyone about who he was. Many of the phrases used in tribute were the same phrases used to introduce him on screen over the past few years: much-loved comic, sparkling raconteur, outrageous entertainer.

His formative performances were stressed – those “zany and usually risque characters he played in countless Carry On films,” as Peter Snow put it on BBC2’s Newsnight. But while his 1980s persona was freely acknowledged, his 1980s work was almost entirely overlooked. If it was mentioned at all, it was in order to illustrate an end point – his final iteration – not as something of merit in itself, or evidence a man whose career was still expanding into new areas or formats.

In April 1987, a year before his death, Williams appeared in an edition of Arena devoted to the subject of the chat show itself, or the “talk show” as the programme insisted loftily (no doubt to Parkinson’s approval). The format required him to join Russell Harty and David Frost – both of whom had interviewed Williams several times – in a discussion chaired by Gus MacDonald. The line used by MacDonald to introduce Williams, “Not just a brilliant talker but also unfailingly funny”, nailed the dual appeal of Williams as both creator and executor of entertainment.

Williams then told MacDonald of his despair at being asked “very standard” questions such as ‘Do you find people recognise you on the street?’ and ‘How do you cope with being recognised?’. “I hear all this kind of rubbish; nobody’s interested.” Here Williams was wrong, for this wasn’t true. People were interested in these questions when Williams was answering them, precisely because he was Kenneth Williams and he answered them like nobody else.

Arena, BBC2, 10 April 1987

The publication in 1993 of an edited selection from his diaries began a process of thickening the emotional texture of Williams’ personal and professional life.

The dominant narrative became one of a man who visited great joy upon millions but great sadness upon himself. It’s a process that continues to this day, in the form of biographies, documentaries, stage plays, TV dramas, even fictional continuations of his life into the 1990s.

But while the shape and reach of these perspectives have been original and sometimes giddy in their elevation, the foundations are mostly unchanged from those laid at the moment of his death: a continuous trench running from Hancock and Round the Horne to the Carry Ons and Just a Minute, and, to represent his entire TV career, Parkinson or – at a push – Jackanory. Once again, his later years barely get a nod.

The ambience of this memorialisation rarely changes. It’s one of light forever fringed with darkness, of fun diluted by unhappiness. Kenneth Williams: the melancholy clown. It was there in the titles of a pair of BBC2 documentaries about Williams broadcast in 1998: ‘Seriously Outrageous’ and ‘Desperately Funny’. It’s never been far away since.

Luckily, thankfully, this is a narrative you can choose to pick up but also choose to set aside. The choice is possible thanks to Williams himself – specifically, that portion of Williams’ career that rarely makes it into the retrospectives: the 1980s.

Because he busied himself on television so much during the last part of his life, and did so across so many types of programme, he left behind a repository of sounds and images large enough for each of us to take from them as much or as little as we wish. More of it appears online each year; the archive is enormous and accessible and never dull. It is perhaps his greatest gift to the nation.

You can find a clip of Kenneth Williams to match your mood. George Melly wrote of Williams in 1968, after watching him on television, that he is someone who can appear all at once “put-upon, vulnerable, loveable, and curiously courageous.” The only common thread is the voice: and what a ravishing thread it still is. Mick Brown captured its essence in The Guardian in 1983, in the kind of sentence Williams himself would have relished the chance to say:

“A high-speed collision of supercilious vowels and mischievous exclamations, part diplomat, charlady and poodle parlour coiffeur, which gallops from St Pancras to Belgravia and back, usually without allowing anybody else to get a word in edgeways.”

The multitude of Williams’ material online is welcome. At the risk of layering the hyperbole on thick, it’s also vital: for Williams cannot be consigned to popular history as chiefly a case study in late 20th century tragicomedy. His body of TV work is too rich in diversity and too full of period detail to be shoved to the back of a pseud’s filing cabinet. It is the work of a one-off.

When introducing Williams on his chat show in 1973, Russell Harty offered the farsighted – and typically lyrical – assessment that his guest was someone whose “remarkable talents and idiosyncrasies” could only have “survived and flourished in England’s green and pleasant land”.

To watch Williams on television is to be reminded of something very particular and precious: that people who emblemise both talent and idiosyncrasy can, from time to time, find a home on the small screen, and can in turn be welcomed with respect and pride.

_______________________________

• Of all the sources I used to help me write this piece, the most valuable by far was The Kenneth Williams Companion by Adam Endacott, in particular its dazzling chronological inventory of Williams’ television career.

• And for those who are interested, here are the 78 different television programmes on which Kenneth Williams made at least one appearance in the 1980s, whether as guest, performer, narrator or contributor. In alphabetical order:

6.55 Special, After Hours, Aladdin & the Forty Thieves, All Star Secrets, An Audience with Kenneth Williams, Arena, Aspel & Company, Bilko on Parade, Blue Peter, Bodymatters, Breakfast Time, Carry On Laughing’s Christmas Classics, CBTV, Chaos Supersedes ENSA, Child’s Play, Choices, Come Close, Comic Roots, Countdown, Cover to Cover, Cross Wits, Day to Day, Daytime, Did You See…?, Elinor, Fame, Friday Night, Friday Night… Saturday Morning, Galloping Galaxies!, Give Us a Clue, Good Morning Britain (TV-am), Harty, Highway, In at the Deep End, Jackanory, Joan Rivers: Can We Talk?, Judi, Live From Two, Look East, Look North, Look Who’s Talking, Looks Familiar, Loose Ends, Money-Go-Round, Nationwide, Newsnight, On Safari, On the Market, One O’Clock News, Opinions Unlimited, Parkinson, Password, Pebble Mill at One, Photo Me, Play It Again, Private Lives, Recollections, Report West, Revelations, Saturday Night at the Mill, Some You Win, Star Turn Challenge, Sunday Best, Sunday Sunday, The Golden Gong, The Paul Daniels Magic Christmas Show, The Pyramid Game, The Six O’Clock Show, The Theatre Quiz, The Video Age, Through The Keyhole, Tomorrow’s World, Watchdog, Weekend, Whizzkids’ Guide, Whose Baby?, Willo the Wisp and Wogan.